Levin defines or describes Utopia as "this strange but touching belief, a belief so deeply embedded in the thoughts and feelings of mankind that it seems to be bred into the very genes." The beliefs vary from person to person, and from culture to culture, but usually comes down to the idea of some place that is idyllic, perfect, and peaceful. Among the first entries into literature you find descriptions of such places, and I dare say oral tradition would carry the belief back much further. Homer describes Olympus:

Outside the courtyard, near the doors is a large four-achre orchard, with a fence on either side. Here trees grow tall in rich profusion, pears, pomegranates, glowing apples, luscious figs, olives in profusion. Their fruit never goes rotten, never runs short, winter or summer, all through the year.The Elysian fields come to mind as well. We tend to associate that concept of the afterlife with the Romans, but like a great deal of ancient Roman religion (all of it?) it owes everything to the Greeks. Homer again describes Elysium:

where life is easiest for men. No snow is there, nor heavy storm, nor ever rain, but ever does Ocean send up blasts of the shrill-blowing West Wind that they may give cooling to men.Of course, the Christian heaven also fits the bill, with its golden streets, its gates covered in jewels, where there is no sickness or death nor sadness, misery, or despair. But it isn't just the afterlife where Utopia is concerned. Where there is a heaven above there is an Eden below, and as Levin points out numerous times throughout the book, where there is an Eden there is a serpent in hiding.

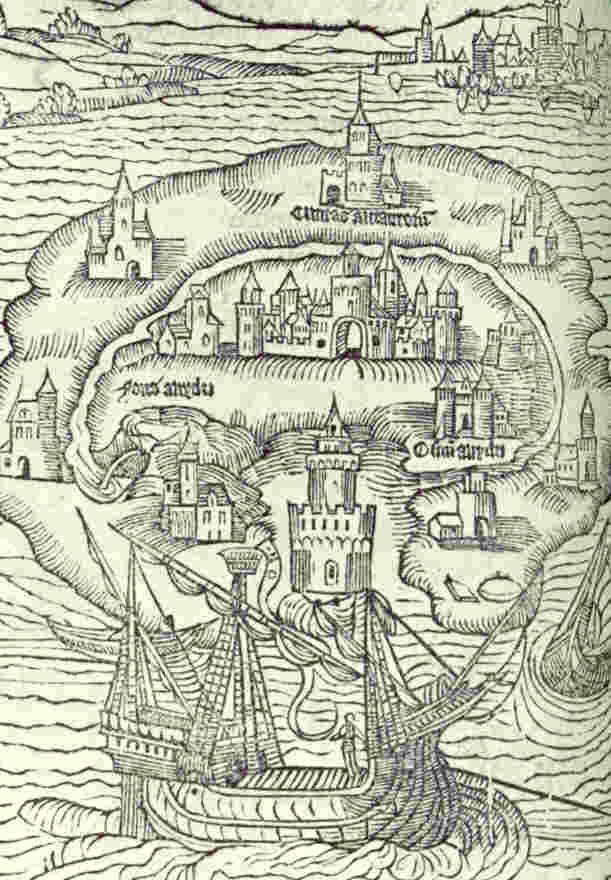

The word Utopia was first used by Thomas More in his book by that title. Broken down the word translates from the Greek to mean "no-place"; a very similar word might be eutopia, which would mean "good-place". That More chose utopia is interesting, because just by using that word itself the question is asked: does Utopia exist? Can it exist?

Utopia is ruled by king Utopos, who created his island state by destroying the isthmus that connected it to the mainland (something that Mussolini thought about doing centuries later with the causeway that connects Venice to Italy. There's something about separation from the world that appeals to many utopians)

The island has 54 cities, each divided into four equal parts, each with exactly 6000 households (this sort of precise mathematics is common in utopias, in Plato's ideal state there would be 5040 households, and no more!). There is no private property, and each household is rotated between families. All goods are stored in a warehouse, nobody having any more claim to those goods than the next person - even here, in 1516, we see a kind of communist haven, where everyone is equal both in class and property. But Utopia isn't really a utopia; after all, there is crime, there are executions, to put it another way, there is a serpent in the garden.

Communism has a strong utopian drive behind it, but then again, probably every political ideology has a fundamental utopian vision. Anarchists think that once government is dispensed with the Sun will shine the brighter, democrats think if only the whole world can be 'converted' to democracy peace will reign. Even Hitler had his grand vision, though of course that utopia had an exclusive membership. And that introduces one of the great utopian ironies: that wherever utopia tries to plant itself blood and pain almost always follow - all the more if two utopias clash. There can be only one! By that view there is often a thin line between utopia and dystopia.

Utopia can be a hope for the future or a dream of the past, the ever present Golden Ages. Some people idealize the years of their youth, and somehow project the innocence of that time upon the whole of society, as if Leave it to Beaver represented the 1950's. Others go much further back, such as Rousseau who, in the years immediately preceding the French Revolution proclaimed that humanity would find its utopia when it returned to the state of Nature from where it came. He imagined an almost Eden-like existence for our ancestors tens of thousands of years ago, living in complete freedom from politics, debt, and inequality. He is thought to have been huge in inspiring the revolution, the instigators of which promised total equality and the elimination of poverty. But when it became apparent that things were not about to change as quickly as the people wanted desperation drove the revolutionaries to a grim finale in the Reign of Terror, where anyone thought to be anti-revolutionary were executed, often by beheading. Over 20,000 people met their end in that time, and finally the revolution, as Levin puts it, ate even its own children.

Future utopias can be pleasant because we don't have to include such atrocities - we are free to let our hopes carry us away. I think one of the greatest and most appealing utopias of the future is found in Star Trek, where humanity has become part of a vast federation of civilizations, all living together in relative peace. But even in our visions of the future we seem unable to keep the serpent out - almost all science fiction utopias have at least a faint dystopian odor, and many unravel in a spectacular way.

There are also utopias of the mind; personal hopes and dreams. Levin describes one dream that almost everyone is familiar with: "This is the dream of instant riches, which most of us have been tempted to dwell on, nobly deciding that we would give large sums to our nearest and dearest, and largesse to needy causes." Perhaps there is a danger in being consumed by these daydreams, but I like this line, where Levin injects a little optimism: "Nevertheless, it is a poor heart that never rejoices, and a poorer one that never muses, half awake and half asleep, for things not really attainable."

But what does it all mean? It seems as if Utopia is in everything we do, every dream we have. Isn't there even a little of it in my desire to travel to Greece and walk among the ruins? Wasn't it in my decision to drive across Canada and return home? It is certainly is full swing during election time (though cynicism is widespread enough now that everyone knows deep down that Justin Trudeau or Obama will certainly not be ushering in any kind of new utopia.) The most obvious cause of our "utopianism" is the world around us, conscious of it as we are in all its injustices and cruelty, poverty and suffering. We all need Utopia in some form or another as a place of escape or refuge. But maybe there is more to it than a simple reaction against a harsh world; maybe Levin is right and such desires are in our very genes, pushing us to imagine something better, and little step by little micro step maybe the optimist could say that things are getting better, says the white male in Canada.

Prologue

I googled utopia for a cool picture to put at the end here, and that is an interesting exercise in itself. Everything from beach paradises to subterranean cities to futuristic cornucopias. My favourite imaginations are of the ring worlds: this is something I heard of first in a radio interview on Quirks and Quarks (!), where the interviewer asked some guy what possible habitations humans could find themselves in far down the road. I think the concept was popularized by Larry Niven - a sci-fi writer who I have never read - and it imagines an enclosed ring that could completely encircle a large planet or even a star.

No comments:

Post a Comment